Ever since I began programming, I’ve been fascinated about source code and its structure. For those unfamiliar, source code is the text in which a person, a programmer, writes instructions for a computer to follow. As with all texts, these instructions can be written in one of many languages as long as both the person writing these instructions and the machine that follows them are both proficient in the language.

Even in the same language different instructions can yield the same final result. I could instruct you to go to the nearest store to pick up a gallon of milk. I could also instruct you to simply keep walking North and pick up a gallon of milk at the first store you encounter. Both of these instructions would yield me a gallon of milk. However, they’re undoubtedly different.

And it is that very difference which fascinates me. While reading source code, I’m not reading an instruction set, I’m reading a story. A story of a world that I can transport myself into and follow along as the main character, dictated by the person who wrote it. If the story is poorly written, it is hard to follow, making it painful to figure out what the ending is. When I write a story, I want other people reading it to not just follow my instructions, but become immersed within the world I’m creating.

When I’m reading source code, I’m not reading an instruction set, I’m reading a story.

I started calling myself a Software Artist. Partly because I wanted to be different and partly because I felt different. However, even with my conviction of declaring myself an artist in my craft, I still struggled when trying to explain to people how source code itself could be considered artistic.

Emotion

One of the first conversations I had on the topic was with my friend and at the time manager Hampton Catlin nearly two years ago. I brought up how I felt about source code and art. We talked about how art should inspire feelings upon the person experiencing it. We got ourselves on a small existential tangent where we pondered if source code itself had emotion, and he went off to code this beautiful commentary aptly titled S.A.D.C.O.D.E.

It was amusing, but it also wasn’t exactly what I meant. The exploration around S.A.D.C.O.D.E. is similar to writing an AI that mimics a depressed person. In other words, the output of the program itself is expressing what would be emotions and, given the relationship with an observer and the technology, perhaps feelings of empathy could ensue.

But my goal wasn’t to mimic human emotion within source code, it was to inspire emotions (hopefully positive ones) onto the reader.

Understanding

One of the sentiments I keep running into is that source code itself cannot be art because most people don’t understand it. Software and technology most certainly can be used to create art. CODAME and this musician are great examples of that. Their program’s output creates a thing which can be interpreted by anyone; music, a game, or a portrait — these things are universally understood.

But poetry is undoubtedly considered art even though it must be written down in a particular language. Would someone object that poetry written in Balochi cannot be considered to be poetry because Balochi as a language is not widely understood?

Regardless, I understand the struggle that people go through with this. I set out to see if I could create a relatively easy, artistic programming language for people to understand. Instead of doing that, however, I found this beautiful programming language called Piet created by David Morgan-Mar.

The above image is the source code in the programming language Piet that solves the Tower of Hanoi problem. That’s right, the source code for the programming language Piet is an image.

Here is the source code/image for a Piet program that outputs the word “Piet” on the screen.

One could say that Piet does a great job at exemplifying how artistic source code can get. However, there’s a problem with this: It gives the illusion of understanding. It’s like listening to a song in French even though you don’t know what the lyrics are saying because you enjoy the part you do understand: the music. Piet gives you a new dynamic of source code that you can appreciate even if you don’t understand how computer instructions work.

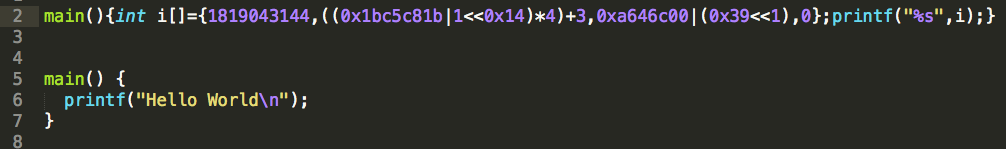

So how about something more traditional? One of the first things that came to mind when trying to answer the question of what is an artistic piece of source code was quines. Quines are programs that, when executed, print to the console their own source code. An interesting extension of quines are programs that output to the console the source code of another program. What that program does, well, that varies.

There is a quine-relay program which, when run, outputs the source code of another program in a different programming language, which, when that is run, outputs the source code of another program in a different programming language, so on and so forth going through 50 different languages until you run the last one where it outputs the source code of…the original program.

Likewise, there are quines which take advantage of the ASCII nature of source code to simulate an ASCII art animation where every step requires you to run the output of the previous program.

Writing quines and their variations are definitely an exploration in creativity and imagination in a world of many constraints to yield an output which is most certainly aesthetic and conducive to some human interaction. That, in it of itself, is most certainly artistic.

However, the artistic appreciation of Piet and quines are not tightly tied to the comprehension and proficiency of the source code. Though extremely intriguing, they do not personally enthrall me. What drives me instead is the story buried in the lines of poetic computer instructions. To truly appreciate that, you have to be proficient in the instruction language the story is written so that you can read, interpret, and critique it.

Social Commentary and Context

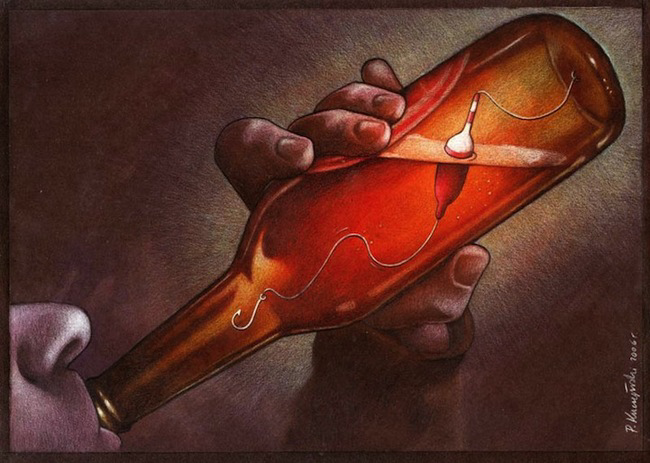

Social commentary is an interesting topic because it is very often used as a sufficient but not necessary attribute for declaring things to be art. The implications behind this is that a poetic or artistic work can offer some sort of commentary on a heavy issue dealing with ethics, politics, or some sort of meaning. This meaning, of course, is heavily contextualized in the world the artist is commenting on. One particular cartoonist that comes to mind who exemplifies this beautifully is Pawel Kuczynski.

His works are thought provoking, commenting on social paradigms that envelops our world which are all too eerily familiar.

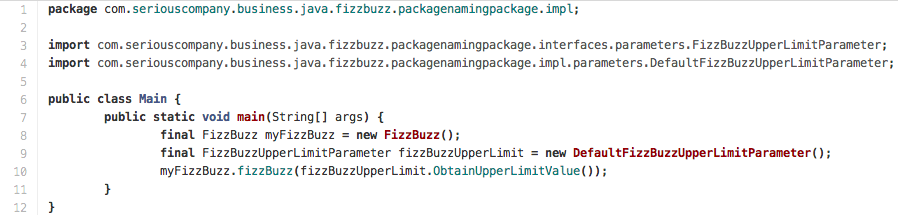

As for source code? Well, something similar comes to mind as well. The FizzBuzzEnterpriseEdition project started by Mikael Kragbæk and in collaboration with many others.

Do you feel anything when looking at this? I certainly do. I feel amused, depressed, nostalgic and yet, affirmed. Honestly, it gives me an emotional roller coaster of feels, and depending on what your experience is with enterprise software, you will get different feelings.

Are you feeling numb though you may understand the Java programming language? Then perhaps you are in need of context. The context of…

- How the programming problem FizzBuzz came to conception.

- How straight forward the source code for the solution actually is.

- How common it is to hear trick questions in programming interviews that are seemingly simple.

- How before the turn of the century, Object Oriented Programming became the hottest style of programming for businesses.

- How one might react in a programming interview if asked to solve a simple problem given that they live in the above context.

- How programmers care so much about code reuse and abstraction that eventually a bible on writing reusable code was written.

- How even though the book covers over 20 different kinds of patterns for reusable code you will most likely only encounter the first three.

- How most of the code you will encounter that makes use of these patterns is probably using them incorrectly.

- How the main purpose of using design patterns themselves is now counter to the use of them.

That is a lot of context, but it is context that I have lived through. As the cartoons of Kuczynski rely heavily on the observer being familiar with the specific context he is commenting on, so too the developers of FizzBuzzEnterpriseEdition rely on the observer to be familiar with the context their code is commenting on. The difference between the two being that Kuczynski covers a more universal context.

If I were to summarize the source code for FizzBuzzEnterpriseEdition, it would probably be the history and volatility of my programming opinions with regards to writing good software. A journey that flashes before my eyes every time I glimpse at a file in it’s repository.

Code for People

I love seeing source code such as FizzBuzzEnterpriseEdition in the world as social commentary of the current state of a particular branch of software methodology. The fact that one can express that sentiment and context using source code definitely elevates the medium to an artistic platform.

However, on a day to day basis as a software engineer by trade, I can’t present a view of my source code that weighs heavy in social commentary. Instead, I pay great attention to detail on the story that I have to convey. Though I know a computer can understand even the most esoteric of stories, I try not to write mine simply for the computer. There is little joy in making art for a critic whose only opinions are “passed” or “failed.” Instead, I write for people. I write source code so that other people are able to read, interpret, judge, and critique it.

Much like nail art, the idea expressed by artistic code is the intention of writing code for another human being to read. A craft, elevated to an art simply because I care just as much, if not, more about it’s interpretation by another human being than the output of it’s interpretation by a machine (which is easily satisfied by comparison).

I want to capture people in the story of my source code’s stanzas in a way that they can easily absorb the metaphors of the world I had to program for rather than having them read the equivalent of a dry source code textbook.

What qualifies as code readability is extremely subjective of course, but in that same realm, so is art.

Are you a Software Artist?

Unfortunately, writing with such intent is not always the route to take. There are most certainly times when writing code as quickly as possible is essential and thoughts of having another human reading your prose are superseded by satisfying the machine quickly and iteratively. Rapid prototyping is most certainly one of these times.

The main benefit of writing artistic code is exploited when working in collaboration with other people. If others have to see your code, it almost seems neglectful to not think about what you want to convey across to another human being with it.

So are you a software artist? Well, do real live people read your prose? Who are you writing for?